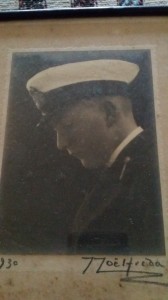

This is a story that lives in a photograph. It is an old picture in a dusty frame, and I think of it sitting on chests of drawers for many years with nobody bothering to look at it much. But now I do.

The picture is of my father when he was fourteen. We all called him ‘Bob’ rather than Dad. I don’t know why, and I’ve never found out where the name came from. He wasn’t a Robert or anything – his real name was Peter. Growing up, I didn’t know anyone else whose Dad was called Bob. The name was a bit magical, it made him special in my eyes.

The picture is of my father when he was fourteen. We all called him ‘Bob’ rather than Dad. I don’t know why, and I’ve never found out where the name came from. He wasn’t a Robert or anything – his real name was Peter. Growing up, I didn’t know anyone else whose Dad was called Bob. The name was a bit magical, it made him special in my eyes.

It is a studio photograph and the picture is set up as a profile silhouette with the photographer lighting Bob’s face from the side against a black background. You can see the photographer’s name at the bottom on the right – Noelfreda (with the accent on the ‘e’). And you can also just see the date on the left – 1930 (which is how I know he was fourteen years old when the photograph was taken).

He is wearing a white peaked hat, and there are markings on his epaulette signifying that he is a Royal Navy cadet. I imagine the formal photograph was taken to mark his completion of the first part of his education and training to become a naval officer. Perhaps he is wearing the uniform for the first time.

So It captures an important transition moment in my father’s life, and his rite of passage from boyhood education to young adult life. It is one of the many things I love about this photograph. I don’t know if the photographer asked Bob to tilt his head forward for the photograph or he chose to do this himself. Whatever I also love his humility in this gesture of looking down.

The young man has passed through the cave of darkness and is emerging into the light. I get a timeless quality, the sun is forever rising in front of my father, even if he does not wish at this moment to raise his head to look directly at it. It always gives me a feeling of confidence: here is my father as my humble guide across the years. Even now I am old, indeed old enough to be Bob’s grandfather in this photograph, I still get this reassurance from him, from the youth entering adult life in humility with head bowed, and forever showing me the way.

Except by not looking at the light directly himself and looking down, and there is a second possibility. Perhaps he is not refusing to look towards the future. Maybe he is in a place of darkness and is refusing to look at the past from where the light comes from the wreckage of history which is on fire. After all Bob was born in 1916. He is a child of the First World War.

In this second possibility the flames of the past are burning in the darkness of the night. The future is being denied my father, and his head is turned away from what is to come. Maybe this turning away is actually an act of wisdom on his part. In 1939 he was twenty three, and by then a Royal Navy officer on active service on destroyer warships. So he was pitched straight into the Second World War, and the ships he was on got involved in fighting, first in the Mediterranean and then on Russian convoys which accompanied merchant ships to Murmansk in 1942.

I don’t know what he saw of the horrors of war, and like many men of his generation, and the one before, he refused to talk about it. I also never saw him wear his string of medals. Like in the photograph his head remained bowed and he kept silent. And each year in November around Remembrance Day I find myself conflicted in my feelings about his submissive gesture in the photograph. Yes, on the one hand in his submission I do feel a personal sense of pride for what he did, and the service and sacrifice of his generation which, I have no doubt, has given me a better life. And on the other hand, I hate his gesture of submission to war and the violent and destructive aspects of men, and the masculine systems of authority whose acts of aggression and folly lead to the death of so many, and wrecked and traumatised the lives of so many others.

Above all I hate his silence, because of course when you don’t speak about shadow things – including the horrors of war – you can’t speak of other loving things as much as you want to either.

And still it goes on today. As I get older, and especially during the Remembrance Day month, I want to speak out more and more passionately against these old aggressive and violent patterns of men and masculinity. I need this photograph of Bob to remind and show me how to be different. Inside we men are vulnerable – of course we are! Inside, my father say, men want none of these legacies of violence and long to be free of them.

I use the photograph of Bob this way to cut through my sometimes conflicted feelings about the past, and what always shines through to me is the tenderness on my father’s young face. So I speak out because I know there is a better legacy from history for men than war. It is this tenderness.

And so I also know Bob’s gift of love.

*Remembrance: this is one of three stories I have to tell about men in my family who mean the most to me – Grandfather, Father, Brother.

Max Mackay-James

Director of Conscious Ageing Trust – growing Diealog Communities to improve the experience and practice of all our ageing, dying, caring and loss. Men Beyond 50 is a special project in Diealog (www.diealog.co.uk) working to reduce isolation and loneliness in older men .